Note from Editors: DSA has recently announced two separate delegations to Latin America: one to Venezuela to attend the Congreso Bicentenario de los Pueblos, an international gathering of socialist organizations in Caracas, Venezuela from June 21st to July 1st; the second to observe the second round of the Peruvian election on June 6th, to ensure fair, democratic practices. In anticipation and celebration of DSA latter delegation, Partisan has translated this piece.

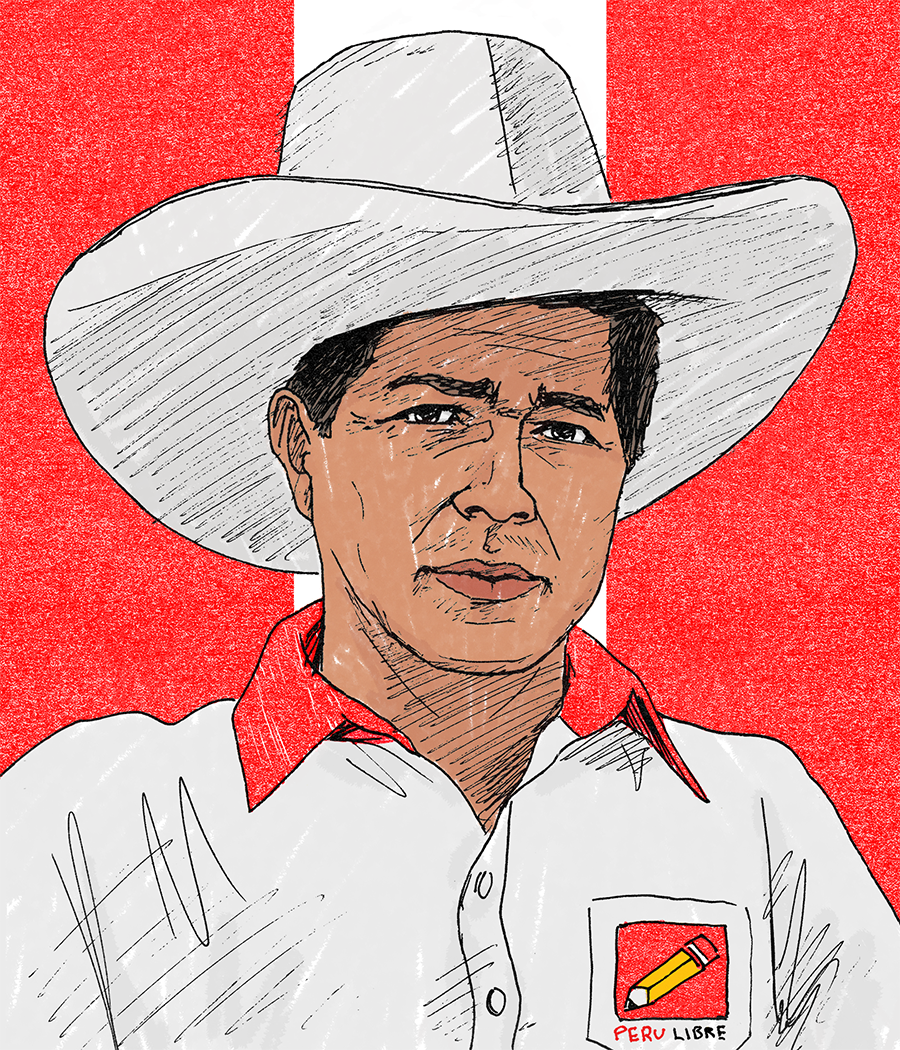

Note from the Author: This article was originally published before the first round of the presidential election held in April 11, 2021. The leftist candidate Pedro Castillo (Peru Libre) won the first-round election, followed by the right-wing candidate Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of the former dictator Alberto Fujimori; both candidates are currently campaigning in a runoff election to be held on June 06, 2021. A few weeks ago, the two leftist parties (discussed below) signed a unity agreement to face Keiko Fujimori whose victory would mean the continuity of neoliberalism. Peruvians are on the verge of a historical moment, after 30 years of neoliberalism there is a unique opportunity to change the course of history, and Pedro Castillo’s victory could lead that change.

In a recent article in Jacobin Latin America, Daniel Siguas has provided us with a very lucid analysis of the social, political, and economic situation in Peru. Siguas also presents a balanced critique of the two progressive forces in the electoral contest: Juntos por el Perú (JP) with Verónika Mendoza and Perú Libre (PL) with Pedro Castillo, both of which are competing against an overwhelming majority of more than a dozen political forces representing the right and the ultra-right.

Like Siguas, I agree that an anti-capitalist horizon will only be possible with the active and transformative participation of popular and social movements. Nevertheless, although both parties draw together some clearly anti-capitalist movements and collectives within their bases, as a whole these political projects still fall far short of truly representing anti-capitalist ideas. At best, they constitute transitional projects at different levels of political maturation.

In what follows, I will try to succinctly examine the economic policy proposals of the two main left-wing forces. This will allow us to show that, both ideologically and programmatically, PL is much more in line with anti-capitalist ideology than JP, although this difference is one of degree and not of kind. These differences, however, do not negate the existence of confluences and programmatic convergences, which we will briefly mention in the final part of this article.

Juntos por el Perú (JP): The Persistence of Neo-liberal Dogma

Prominent heterodox economists, such as James K. Galbraith, Jayati Gosh, and Matias Vernengo, along with other intellectuals, have publicly endorsed the candidacy of Veronica Mendoza (JP). This support is laudable and important for the Peruvian left and its proposed response for confronting the devastating political, social and economic crisis that the country is going through, a correlate of more than 30 years of neoliberal policies further intensified by the pandemic. However, as I have mentioned, JP is not the only progressive force in these electoral races, nor the only one with a chance of reaching the second round. In reality, JP represents the more “conservative” position within the left, much closer to the ideals of social democracy than to Marxism. As such, identity politics constitute the dominant and cohesive force in its programmatic proposal.

Economically, although political leaders and economic advisors rhetorically question neoliberalism, their proposals have a certain continuity with it. Thus, against a backdrop in which there is no radical break with neoliberalism, JP’s proposals are embellished with expansionary fiscal policies aimed at overcoming the current economic and social crisis, a necessary but insufficient condition to envision a post-neoliberal horizon. JP economists insist, as do neoliberals, that fiscal deficits will have to be adjusted as long as the “recovery ” from the crisis lasts, in contrast to the policies of functional finance or full employment that heterodox economists have been actively proposing. The same fiscal adjustment (“fiscal consolidation”) that the Central Reserve Bank of Peru (BCRP), a bastion of neoliberal technocracy, establishes as an economic policy goal in the Multiannual Macroeconomic Framework 2021-2024.

One of the most controversial aspects of JP’s proposal is its repeated insistence to continue supporting the neoliberal myth of an independent central bank, a myth imposed by the Fujimori dictatorship and its technocrats. It is safe to say that the heterodox economists who signed JP’s endorsement unanimously disagree with the perpetuation of this myth. In fact, both post-Keynesianism as well as other heterodox schools have not only systematically exposed this conceptual fallacy, but also advocated a dual mandate (full employment and monetary stability) subject to the needs of the masses and not the interests of big capital. The left must understand, once and for all, that policies, as well as monetary and fiscal instruments, are nothing more than the ensemble of power relations, and therefore of class, and not merely technocratic mechanisms that must be shielded from political influence, as self-serving neo-liberal and neo-classical economists would like to claim. Perpetuating this myth only leads to inaction and capitulation to neoliberalism and its technocrats, entrenched in the BCRP, but also to the loss of a key tool for the active promotion of economic development, which the country so badly needs.

Similarly, JP proposes to continue with the Reactiva Peru program, implemented by the neoliberal government of Martin Vizcarra as an economic response to the pandemic; a measure that has disproportionately favored big capital, to the detriment of small and medium-sized enterprises and the working class. According to Oscar Dancourt, JP’s economist, this program is “a great monetary policy tool” in the face of the crisis triggered by the pandemic, and he blithely insists that it “has no negative side effects”, as if the “temporary” layoffs of workers carried out by the companies benefiting from Reactiva Peru amounted to a minor inconvenience.

These coincidences and continuities only generate a certain skepticism about JP’s anti-neoliberal credentials and therefore, in addition, fade away the vision of materializing the anti-capitalist horizon.

Perú Libre (PL): Extractivist Continuity and Class Essentialism

PL is a party that declares itself Marxist-Leninist and Mariateguist, with a marked anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist position, but also with clear popular and indigenous roots. However, this radicalism is tarnished by the absence of identity policies and a social conservatism foreign to the contemporary anti-capitalist ideology. These contradictions need to be resolved in favor of a political project that transcends class essentialism without abdicating Marxist principles. This does not however mean to accuse PL and Pedro Castillo of representing a parochial, self-absorbed, and folkloric left; a classist, and even racist, rhetoric, which certain progressive sectors have uncritically echoed.

PL’s economic program is based on the progressive Latin American experiences, especially those of Ecuador and Bolivia, and is synthesized in what PL calls “Popular Economy with Markets“. A proposal that reclaims the State as the main actor of economic and social development, in a bid that transcends both the neoliberal subsidiary state, as well as the regulating State of JP’s social-democratic program.

PL’s positions range from state regulation of the market, state business participation, state planning, to the nationalization and state ownership of strategic sectors. Priority is given to national production and domestic markets; improvement of tax collection through a progressive tax scheme, for which they also seek a renegotiation of (constitutionally binding) legal contracts with transnational capital; strict control of the repatriation of profits, encouraging its reinvestment in the country; as well as the renegotiation of public and private foreign debt, prioritizing the internal social debt.

Pedro Castillo, PL’s presidential candidate, is a public and rural school teacher, peasant, and indigenous. Perhaps, for this reason, PL’s educational proposal is extremely ambitious; it seeks to increase spending on education to 10% of GDP, which would allow investments in infrastructure, equipment, and the improvement of teachers’ salaries. This is supplemented with policies to fight illiteracy, reformulation of curricular programs for educational decolonization, a public and quality university system, among many other proposals. PL also proposes the restructuring of the health system and its transition to a “universal, single, free and quality” system, in addition to regulating the private health system through a “single tariff” and anti-monopoly rules.

PL supports the continuation and possible expansion of the extractivist frontier; this, together with the absence of identity policies, represents the transgressive aspects of a truly anti-capitalist project. While recognizing the importance of a wage-led growth model, PL considers what they call “sustainable extractivism” as a necessary condition for economic growth. However, the limits of the extractivist model under both progressive and neoliberal governments have been widely discussed. PL needs to overcome this logic and embrace a post-extractivist model of productive diversification that is also socially and environmentally sustainable.

Similarities and Convergences

In spite of these differences in degree regarding the anti-capitalist positions of both parties, JP and PL have a common progressive vision with many similarities and convergences, although with differences of emphasis. Both forces take up the popular clamor for a new Constitution through a Popular Constituent Assembly, the starting point to dismantle the neoliberal State; productive diversification and promotion of small and medium agriculture, as well as the implementation of a development and promotion bank; recognition of labor rights and implementation of a public social security system. On this last point, the elimination of the private pension system (AFP), a disastrous legacy of Fujimorism, and the implementation of a public system that guarantees decent pensions is an urgent social demand. Similarly, direct payments to families (Universal Basic Income) to cope with the acute economic crisis caused by the pandemic and neoliberal austerity policies are of extreme importance.

The greatest challenge for the Peruvian left is to dismantle the neoliberal State and move towards an anti-capitalist horizon, an unavoidable task that demands a joint and coordinated effort. This would require a broad coalition of the left. Unfortunately, this is not possible this close to the elections, however, let us hope that the second round will not only allow this convergence, but also the electoral victory.

Alejandro Garay-Huamán, Peruvian, PhD candidate in economics at the University of Missouri – Kansas City (USA).

Originally published in Rebelion as “Los dilemas de la izquierda peruana: entre el socio-liberalismo y el esencialismo de clase“

Translated by Marvin González