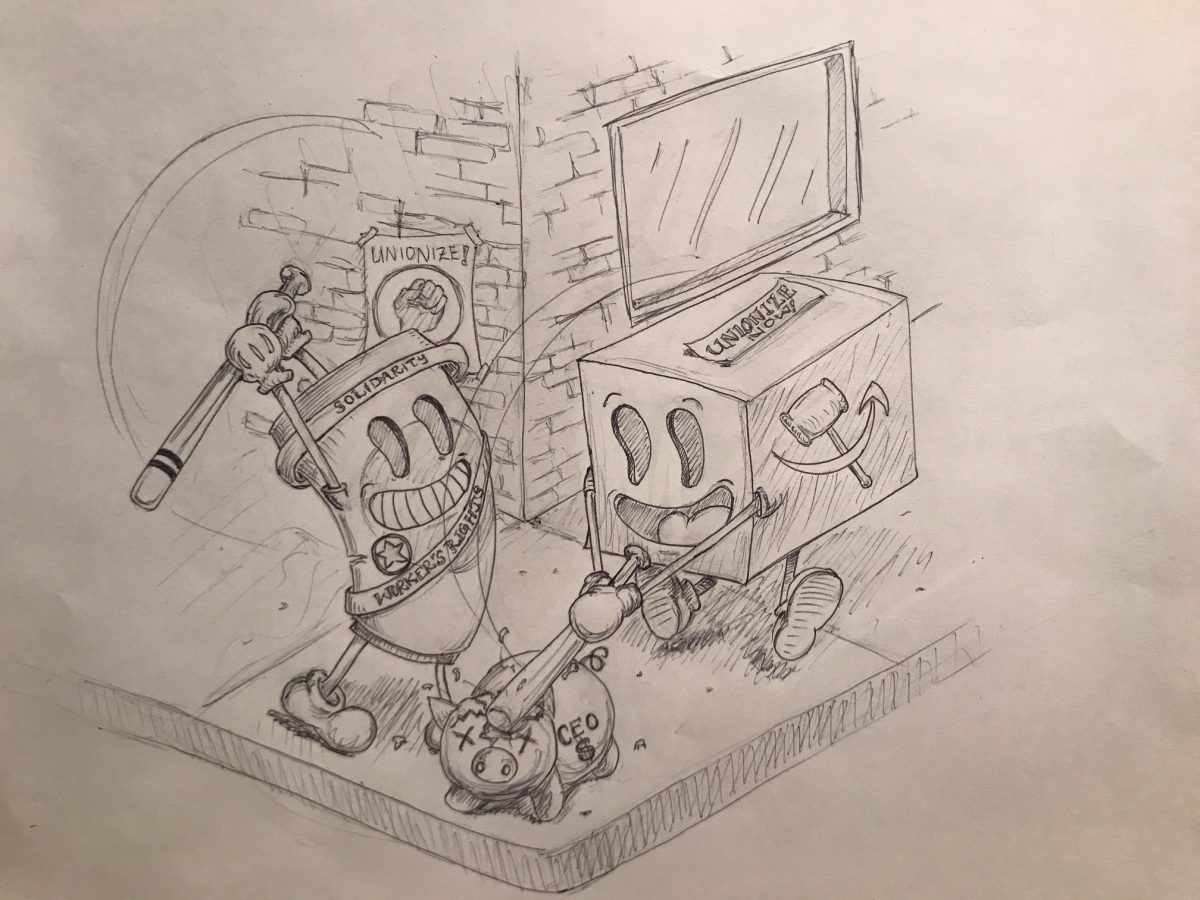

In an article on the three month long Starbucks strike at 874 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts, long time union member and organizer, Steve Gillis, wrote, “in over 40 years of partisan covering of every Boston-area strike since President Ronald Reagan busted PATCO (the former union of air traffic controllers) in 1981, this reporter has never experienced such a political, anti-capitalist, vibrant, united front of socialist-minded workers materialize in defense of a strike—conscious of themselves as a class force and optimistic about a victory.” Gillis might well have extended his assessment to the ascending labor movement at large, which coalesced around the strike over the summer of 2022. Starbucks workers, workers from other recently unionized cafes (Darwins and Pavement in Boston), workers from recently formed graduate students unions (MIT and Boston University), and socialist and communist organizers would staff the picket line all day and everyday, rain or shine. The 24/7 picket was designed to prevent Starbucks from reopening the store with scab workers, and to halt deliveries (with the solidarity of the Teamsters, who would refuse to cross a picket line).

The Starbucks workers are not alone, both in terms of unionizing and carrying out strikes. Workers at Pavement Coffee House, a Boston coffee chain, announced the formation of a union in June 2021, and workers at Darwins Ltd., another Boston coffee chain, followed shortly thereafter in September 2021. Other cafe unions in the area, like the one formed by workers at Diesel Cafe, Bloc Cafe, and Forge Baking Company in Somerville (since they share the same owner), also emerged. The unions at both Pavement and Darwins predated the Starbucks union, which formed in early 2022, and while neither went on strike, Darwins’ workers performed a “walk out” in April 2022 which led to concessions from management. The graduate student union movement in Boston has been brewing since before the Pandemic. MIT and Boston University graduate students have been fighting to form a union since the late 2010’s, and are finally beginning to see the fruits of their labor. Harvard University graduate students, who have been unionized since 2018, went on strike in December 2019, and then again in the fall of 2021. Even workers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston have now formed a union, and went on strike in November 2021 to highlight their demands and importance to the museum.

I am a library worker at a major university in Boston, and my coworkers formed a union prior to my hiring. They began the process in late 2019 and early 2020, and we negotiated our first contract earlier this year. Speaking with my coworkers, their motivations for forming a union were simple: they were exploited and overworked, underappreciated by management, and earned low wages despite rising costs of living in the Greater Boston area. Capitalism is generally defined by the contraction between labor and capital, embodied by workers and the bourgeoisie, where the former are exploited by the latter. The natural response to this state of affairs for workers is to form a union to defend themselves from the predatory behaviors of the bosses. Of course, the union alone does not prevent this exploitation, but tries to minimize it. Capitalism is also defined by a division between manual and intellectual labor, where workers carry out the former, and bosses and management carry out the latter. In any industry or workplace, the workers are treated as the mules who are expected to carry out any decisions made by the bosses, and workers are given zero or little input towards these decisions. Things came to a head at my library during its renovation, when management would ask library workers for their input and preferences on the new building design, but ended up completely ignoring them, despite the fact that they are the ones who would actually work in the space they are designing. Workers would have a better understanding of what the building design should actually look like, and, in the end, management ignoring their advice contributed to all sorts of problems that could have been avoided.

My own experiences in union formation and wage labor, combined with my political commitments as a communist, made me curious about what was happening in other workplaces. Why were they unionizing? What did their processes look like? What are the political commitments of the workers involved in unionization? How can this movement sustain itself beyond the mere attainment of a contract? And lastly, and perhaps most importantly, can this movement coalesce into a larger political force in the struggle against capitalism?

Black Lives Matter, The Bernie Sanders Movement, and the Decline of the Capitalist Economy

It’s impossible to situate the rise of the union movement without connecting it to the conditions that give rise to it, and the formation of these unions has largely been driven by younger workers. In his piece in April 2022 on the formation of this new labor movement, John Logan says, “both the Starbucks and Amazon-Staten Island campaigns have been led by determined young workers. Inspired by pro-union sentiment in political movements, such as Bernie Sanders’ presidential bids, Black Lives Matter and the Democratic Socialists of America, these individuals are spearheading the efforts for workplace reform rather than professional union organizers.”1 Millennials and Generation Z were brought into a world shaped by 9/11 and the Iraq War, The Great Recession of 2008, rapidly escalating climate crises, police massacres of black individuals, the rise of fascism, and, most recently, a global pandemic that has taken the lives of millions. Additionally, they have been raised with the knowledge that they will never attain the economic benefits of the previous generations. Granted, those benefits were powered by imperial plunder at the height of the labor movement in the middle of the 20th century. As Lenin observed all the way back in 1917, the development of a middle class and labor aristocracy was made possible by the hyper-exploitation of workers and peasants in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This, along with heightened class struggle in the mid-20th century, and the peak of labor and communist organization in Western countries, forced the capitalist powers to negotiate a truce with the working class. It was only the defeat of the labor and socialist movements in the 1980s and 1990s that allowed the capitalists to strip back these benefits. Millennials and Gen Z were born into this capitalist offensive and the decimation of the Left.

The declining capitalist system, and the effects it has had on the younger generations, was acknowledged by the workers I spoke to. Willow Montana, a worker at a Starbucks in Brookline, Massachusetts, told me they believe that younger people possess a more radical set of politics due to these circumstances. Montana said, “I think younger people now are coming up more with that [anti-capitalist] mindset, especially with climate change and a lot of things in our future looking bleak.” Spencer Costigan, one of the lead organizers at the 874 Commonwealth Avenue location which went on strike for three months, told me that, “young people tend to be a little more with it [workers struggles and radical politics] because they understand that we’re fucked. We don’t have the benefits that our parents and grandparents had. So it’s easier to convince them that they’re getting a raw deal because they’re experiencing it firsthand.”

I believe the union movement is a continuation of the shift in political consciousness produced by the Bernie Sanders movement and Occupy Wall Street. Occupy advanced the slogan of the 99%, which would become central to Sanders’ campaign rhetoric, and this is the closest thing to the Marxist concept of class contradiction becoming mainstream in decades. Sanders’ loss, or sabotage by the Democratic Party, has radicalized hundreds of thousands in the United States. His losses were partly responsible for the influx in DSA membership from 2016-2020, while also demonstrating the limits of electoral politics within the Democratic Party. Montana told me, “I was more of a liberal when I was younger before realizing none of that actually works [voting for representatives] and that you have to actually do the fighting yourself from the ground up. These politicians are not going to save you, and as much as I really wanted Bernie Sanders to help, I think not putting our faith and trust in politicians will hopefully be the new norm going forward.” Montana added that the struggles and failures of the Biden presidency have only increased this insight, and thinks it has awakened many to the reality of the limits of electoral politics. Montana contrasted electoral politics with workplace organizing, saying, “organizing is something that I can do for myself, for my coworkers, for other people like me, and hopefully for people in my surrounding area who need help organizing, even if it’s not Starbucks.”

Costigan also grew up a liberal whose perception of politics was defined by the belief that Democrats were fundamentally good, while Republicans were evil. She said, “I definitely had that mindset for longer than I would’ve liked, and it wasn’t until I was almost out of high school that I realized Democrats are actually evil and twisted as well.” When I asked Costigan if she saw the union movement as being in continuity with previous political struggles, she was emphatic.

“Absolutely. Working class movements are all connected by a shared set of issues that only they understand and that only they can fix because the capitalist class is not interested in fixing those issues. If they did, then they would cease to be capitalists. They would be conceding all of their power, and that wouldn’t make any sense. So by the nature of these being working class movements, they’re naturally connected, just as this movement is connected with every struggle of oppressed people finding a modicum of dignity in this country.”

Rupture: the Pandemic

The Pandemic changed everything, and it is arguably the most pivotal moment of the twenty-first century. Our entire world and political conjuncture has been shaped by it: mass death and the failure of governments to protect people from the virus, the Great Resignation, the George Floyd rebellions (the biggest since the 1960s), and, now, the emerging union movement in Boston and the rest of the country. While there were already trends toward greater militancy in the labor movement, even if union membership is still declining on the whole, the pandemic completely shifted individuals’ perception of work and their relationship to it. As a result, “record numbers of American workers have quit their jobs in what the media has dubbed the “Great Resignation”. According to the US Labor Department, 4.5 million workers voluntarily left their jobs in November 2021. The number of monthly quits has exceeded three million since August 2020, and the trend shows no sign of slowing down.”2 Students and a certain strata of workers were displaced from their routine and workplace, and shifted to working from home. Working from home highlighted how much individuals’ time is disproportionately spent in the workplace than with one’s family and friends, or compared to spending time on personal hobbies and interests. The pandemic also highlighted how pointless some jobs were in the grand scheme of things.

However, workers in hospitals, grocery stores, public transportation, schools, and other jobs deemed essential to the overall functioning of the economy were forced to bear the brunt of the pandemic, risking the health of themselves and their families or roommates just for survival. Kate Morgan, in her article on the great resignation, quotes Melissa Villareal, a teacher in California, who says, “it became so clear that this isn’t about my health, the health of the kids or the mental wellbeing of anybody. It’s a business and it’s about money. The pandemic ripped that veil from my eyes.”3 The pandemic flipped the public perception of service workers – previously, service jobs were seen as simple and unskilled, and thus deserving of low wages and benefits. During the pandemic, service jobs were now hailed as essential and heroic. This discrepancy did not go unnoticed by workers, especially since they were not being adequately compensated for their essential labor. While workers did receive hazard pay, which expired in most workplaces by the summer and fall of 2020, it only amounted to an extra few dollars an hour. Morgan says, “throughout the pandemic, essential workers–often in lower paid positions–have borne the brunt of employers’ decisions. Many were working longer hours on smaller staffs, in positions that required interaction with the public with little to no safety measures put in place by the company, and, at least in the US, no guarantee of paid sick leave. It quickly burnt workers out.”4

When speaking with cafe and grad student workers, they were in unanimous agreement on the central role of the pandemic is driving the formation of their unions. Noelle Gulick, a worker at a Boston Starbucks, told me, “the pandemic had a lot to do with the working conditions that made people want to file for unions… it really showed the idea of an essential worker that came out with the pandemic. We were deemed essential just because we didn’t really have the option not to work.” Gulick said that working in a pandemic was worthwhile initially because of the hazard pay, but that expired after two months for her store. This indicated, “that conditions were back to normal even though the pandemic was getting worse. They put up plexiglass in front of the customers, but the conditions were always changing. For example, customers at first had to wear masks, but then they didn’t have to wear masks. The safest option for being open was running the drive-through, but quickly opening up the cafe showed that there wasn’t any regard for workers’ safety.”

Like Gulick, Montana agreed that the pandemic played a significant role in the unionization of their store. While Montana’s desire to unionize was motivated by a general commitment to socialist politics and unionization, many of their coworkers were driven by frustrations with working conditions during the pandemic. Workers wanted customers to have to wear masks after the mandate expired, and felt like their safety wasn’t prioritized by management. When I asked Montana why so many cafes were unionizing at the same time, they said, “I think people are tired of being taken advantage of, and I think it’s more obvious now than it has ever been before that we’re being exploited in a lot of ways. Especially in places like restaurants and cafes, and not many are more exploited than a restaurant or kitchen worker, or even just the food industry in general.” Like Gulick, they pointed out the discrepancy between being labeled essential workers by the media and politicians, while earning low wages and enduring unsafe working conditions.

The story is similar in graduate student organizing. Casey Grippo, a PhD student at Boston University, told me that the pandemic jump started their union campaign. The old campaign was still going before fizzling out early in the pandemic, and the new campaign re-emerged in response to BU’s covid policies. Grippo told me that in 2020, especially the fall semester, there were a lot of questions amongst workers about the ethics behind having students back on campus. The grad students were not pleased with returning to campus because they were put in extremely uncomfortable conditions. Grippo said, “I came to BU that semester, and my introduction to BU was being told that if I don’t move to Boston in the middle of the pandemic, I wouldn’t receive my stipend despite the fact that everything I was doing was completely online. There were just a lot of policies that affected us directly and made no sense, and, so, I think people rallied behind that as a way to both support immunocompromised coworkers, but also as a way to say, ‘wow, BU is really disrespecting us here’.”

One of the most frustrating aspects of in-person work during the pandemic was the changing working conditions dictated by management. I worked in person at a public library during the pandemic, and at first we had a curbside pickup process where patrons could request books and pick them up without any contact. This allowed both staff and patrons to safely interact and continue library circulation. But once Covid cases began to drop, the library made the decision to reopen to the public without consulting any of the workers, sparking dissatisfaction. Gulick experienced a similar process at Starbucks, saying, “At first we were only drive-through, and then we went to mobile borders and set up a shelf at the door and put all the mobile orders there for customers to pick up. After a month of that, we let customers in the store, but still just mobile orders only. Then we opened back to a full cafe before COVID cases spiked again again, so we shut down the cafe. There was so much back and forth, and conditions were changing so regularly that it was hard to even keep up.” Risking one’s health and safety during a pandemic, combined with management dictating working conditions despite not working with the public themselves, was infuriating to many workers and exacerbated their grievances.

Returning to Morgan’s article on the Great Resignation, she says, “although workers have always cared about the environments in which they work, the pandemic added an entirely new dimension: an increased willingness to act.” This has resulted both in widespread resignation, where workers have sought jobs in new industries, and a rise in militant union activity. In his article on the labor movement, Chris Maisano observes, “In 2021, we witnessed a modest increase in the frequency and visibility of collective action in the workplace. Tens of thousands of workers, union and nonunion alike, challenged employers through protests and strikes across sectors and in many different geographical regions. Workers in health care and social assistance, education, and transportation and warehousing led the way, but they were joined by workers in hotels and food services, manufacturing, and other industries.”

Conclusion: Politics and Struggle

I believe that the last three or so years of union formation are of significant importance for those invested in communism and emancipatory politics. Union formation is occurring in industries that have typically not been unionized (cafes) and at mega-companies who are historically adept at union busting (Starbucks and Amazon), and there is a militancy that has not been present in unions for a while with spontaneous strikes and bottom-up actions. Logan says, “one would be hard pressed to find many experienced organizers among the recent successful campaigns. Instead, the campaigns have involved a significant degree of “self-organization” – that is, workers “talking union” to each other in the warehouse and coffee shops and reaching out to colleagues in other shops in the same city and across the nation. This marks a sea change from the way the labor movement has traditionally operated, which has tended to be more centralized and led by seasoned union officials.”5 Furthermore, this new union formation coincides with a societal re-evaluation of the meaning of work, which was heightened by the pandemic and a declining economy, and it also dovetails with the rise of socialism in the US, represented by the Bernie Sanders movement.

Sylvain Lazarus, a French political theorist, has advanced a conception of politics based on the capacity of all individuals to think.6 In contrast to some forms of Marxism which would seek to import older forms of organization (like the Leninist party-form) into our conjuncture, he argues that forms of organization arise in particular conjunctures. For the Bolsheviks, this was the party-form which was oriented around the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and whose sites of politics were the Soviets and the Party. The Maoists’ conception of politics was oriented around the Protracted People’s War against the Japanese imperialists, and their sites of politics were the Army, Party, and United Front.7 Lazarus argues that once a political sequence inevitably ends, so does that mode of politics. Instead of trying to import these modes into our own conjuncture, we need to produce our own modes of politics. One way to do so is by investigating contemporary social movements and observing the forms of self-organization that come into being. Two particularly stand out to me: tenant organizing and the new forms of labor organizing, and both directly challenge, or can challenge, the antagonistic class relations that define capitalism. The question for contemporary communists is how to engage and intervene within these movements.

A big question for this union movement going forward will be how to sustain their momentum, as the workers are up against companies like Starbucks and Boston University, equipped with armies of lawyers used to grind contract negotiations to a halt. Or in other words, they will try to turn union negotiations into a protracted battle that saps the energy and morale of the workers. Workers are well aware of this reality, and are intent on maintaining the movement going forward. When I asked Costigan where Boston Starbucks Workers United will go next after their strike victory, she told me, “When we fight, we win, as the saying goes, so I’m pretty confident that going forward we’re gonna see a lot more aggression from the Starbucks union, and I’m super stoked for it. I think people are realizing that there’s something they can do about the abuses that they experience. I don’t think that our store is the vanguard of the working class or anything, but I’m very hopeful that this is the first step in what will be more drastic steps moving forward.” For Grippo at Boston University, a big challenge will appear after a contract is secured. They told me, “I think what it comes down to is the democratic structures of our union, which will play a large part in sustaining that [momentum]. I think that’s probably true of every organization–if the structures are made so that decisions and conversations are satisfying to people, it’ll persist more so than if it’s not satisfying and it’s just a vote you get and you pick yes or no and you move on with your day.” The energy to sustain this movement, whether through expanding the quantity of unions, securing contracts, or expanding the struggle beyond mere unionization, is definitely present amongst these workers. In the fight going forward, we ought to heed the wisdom of the late Mike Davis, who eloquently stated, “I manifestly do believe that we have arrived at a ‘final conflict’ that will decide the survival of a large part of poor humanity over the next half century. Against this future we must fight like the Red Army in the rubble of Stalingrad. Fight with hope, fight without hope, but fight absolutely.”

- John Logan, “A New American Labor Movement,” The Conversation, April 1, 2022.

- Chris Maisano, “Is this the Labor Movement Back?” Catalyst Journal, Winter 2022.

- Kate Morgan, “The Great Resignation: How Employers Drove Workers to Quit,” BBC, July 1, 2021.

- Morgan, “The Great Resignation.”

- Logan, “A New American Labor Movement.”

- Sylvain Lazarus, “Can Politics Be Thought in Interiority?”, Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, Volume 12, no.1 (2016).

- Lazarus makes these arguments in “Lenin and the Party” in Lenin Reloaded (Durham: Duke University, 2007).