In December 1965, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) launched its first boycott targeting grape growers in Delano, California. Filipino farm workers organized by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) had announced a strike in September of that year, rapidly joined by the NFWA, to demand higher wages, better working conditions, and the right to unionize. Grape growers, however, hired scabs and were able to complete the fall harvest despite the strike.

The conditions surrounding the strike were unfavorable. The workers lacked basic legal protections and were easily replaceable; the AWOC and the NFWA, which soon merged into United Farm Workers (UFW), were young organizations still finding their footing and building their own capacity. Therefore, a broader strategy was needed. The organizers launched the boycott as a way to extend the struggle beyond their immediate context, connect to the national civil rights movement, and build economic pressure that picket lines alone were not able to achieve.

Over the course of the next five years, organizers and volunteers fanned out across the country to persuade consumers to boycott table grapes and pressure retailers into only selling union grapes. Volunteers canvassed to build support, passing out flyers at stores and engaging shoppers as they entered. From 1967 to 1969, US grape sales dropped between 30% and 40%. An estimated 14 million people boycotted the grapes, and many stores adopted a “union grapes only” policy. In 1970, the major grape growers in the area agreed to negotiate and sign contracts with the UFW.

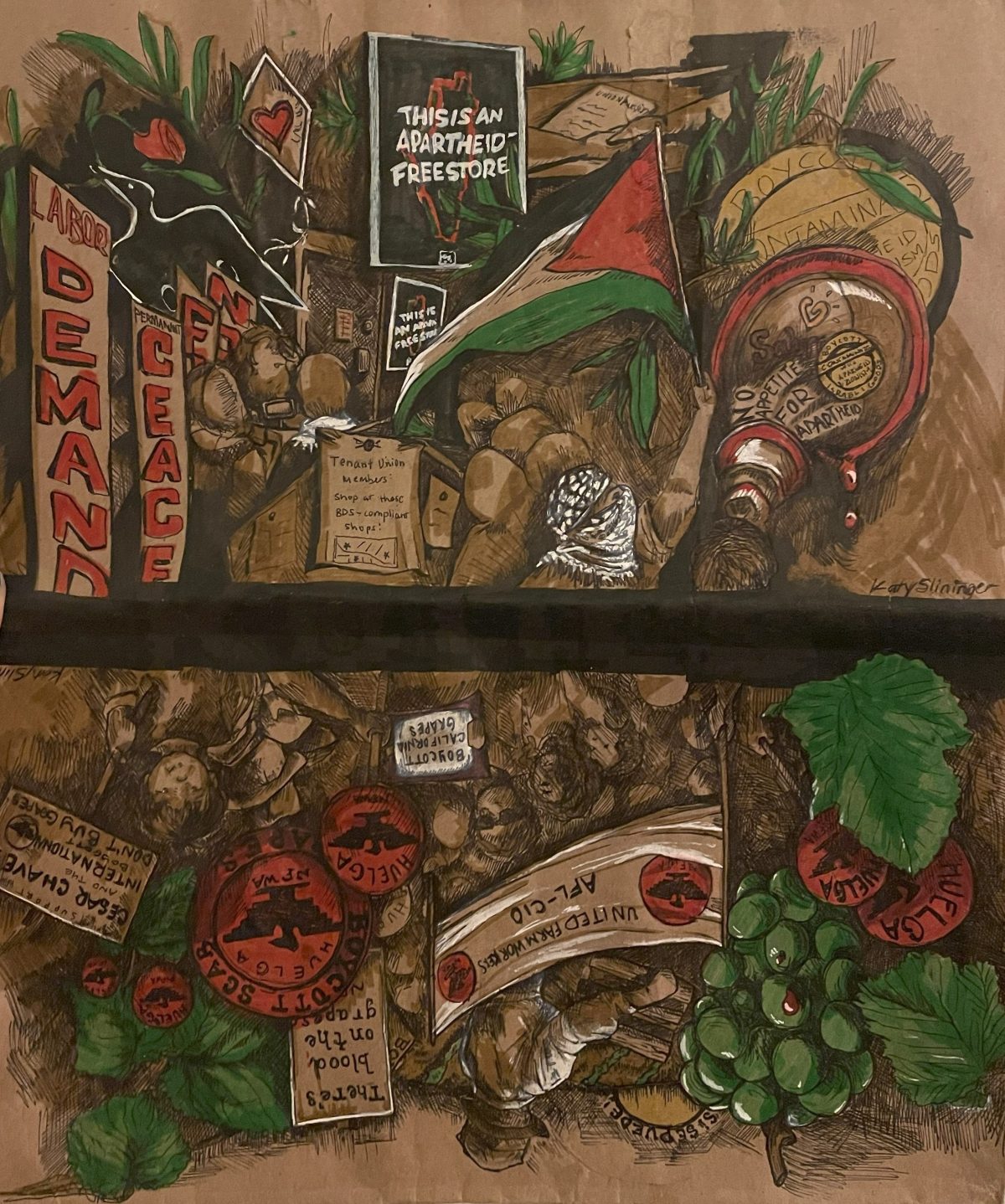

It was with the example of the Delano grapes boycott in mind that, in May 2022, the Palestine Solidarity Working Group launched No Appetite for Apartheid, a boycott campaign targeting the Israeli food industry as well as other food-related companies complicit in the Zionist project. The main tactic of the campaign is canvassing local stores and asking them to pledge to become Apartheid-Free Stores by dropping any brands on our boycott list that they may be carrying (or pledging to not carry them in the future).

By centering the campaign around canvassing and engagement with stores, we were hoping to break with the liberal version of boycotts that requires individuals to act as moral consumers and “vote with their dollar” to punish brands that do not conform to their personal political preferences. Many of us who come from a background of BDS organizing have found that the movement often struggles to identify tactics beyond sharing information about an ever-growing list of brands to boycott, largely with people who are already supportive of the cause of Palestinian liberation.

The lack of mass political practices in the United States has allowed the language of individual consumer awareness to become the dominant form of thinking about exerting economic leverage through boycotts. There is, however, a rich history of boycotts being used by mass movements through community and labor organizations. We considered the example of the Delano grape boycott to be instructive because it engaged and mobilized a nationwide network that reached into local communities, and convinced retailers that complying was in their economic interest by organizing a community base that was willing to collectively withhold purchases of non-union grapes.

Certainly, such a campaign today faces a much harsher terrain. The UFW was operating against the backdrop of the civil rights movement and was able to nationalize the struggle of farm workers in California by connecting it with concurring mobilizations and organized communities in other parts of the country, including through support by labor unions. In the context of widespread disorganization today, and given the relative lack of support for the Palestinian struggle until very recently, No Appetite for Apartheid has a much steeper hill to climb.

Nonetheless, the first few experiments within the campaign show a path to imagine what bringing back a mass approach to boycotts in the context of BDS could look like. The student organization Students for Socialism at the University of South Florida has organized more than 50 local businesses in Tampa to commit to refuse products from the occupation, and is organizing the local community to shop at Apartheid-Free Stores through a BDS pledge. In Connecticut and Broward County, FL, the trust established through repeated visits to stores facilitated mobilizations for rallies and involvement into political education and mutual aid events of Arab and immigrant communities, whose social fabric predominantly white DSA chapters are otherwise scarcely integrated into.

The current surge of support for the Palestinian struggle has given the issue a new prominence within sectors of the organized left where it recently played a minimal role. Comrades across the country have been thinking about how to use existing organizational capacities built through other organizing projects to support Palestinian liberation. For example, a tenant union could take the lead on engaging with local stores to make a boycott ask — the organized structure of a tenant union provides leverage, as tenants can promise to patronize a supportive store and vice versa avoid one that does not comply. At the same time, this process of engagement can make a tenant struggle visible and build support for it in new sectors of the local community.

While the campaign so far has largely relied on making a direct ask to small business owners of primarily Arab- and Muslim-owned family stores, there is potential for worker-led actions in larger stores. Comrades in a few locations are interested in experimenting with labor-driven strategies for the campaign — for example, by having a local EWOC group or unionized retail workers connect with workers at non-union grocery stores and support them in pressuring management to comply with the boycott (and in the process, potentially fostering the structures to support workers’ organizing on other issues). These approaches will have to be tested, but there is potential for Palestine to be a catalyst that galvanizes labor organizing, particularly among Arab and Muslim workers.

When the Palestine Solidarity Working Group launched No Appetite for Apartheid, we were looking for ways to break out of two dominant modes of organizing for Palestine: the first relies on campaigns making demands to completely hostile actors who are unlikely to be movable in the immediate future — for example, a divestment campaign on a college campus or targeting a pension fund. While these campaigns can politicize new people around the Palestinian struggle, strengthen coalitional networks, and build organizing muscles, they are often unwinnable and can have a disorganizing effect once the campaign exhausts the tactics that participants are willing to engage in.

The second consists of increasing political education about Palestine to find new allies in adjacent movements, who may now be open to individual asks such as boycotting products on the BDS list — for example, by highlighting the connections between the Palestinian struggle and other domestic struggles such as housing and racial justice. While building solidarity across issues is absolutely crucial in a context where Palestinian communities are a small minority, the risk is to default to the ‘activist networking’ mode of organizing that cannot break through the bubble of already-politicized people.

On the other hand, No Appetite for Apartheid aims to center external-facing tactics to build an organized base of support for Palestine in our local communities, and allow ordinary people to take internationalist solidarity into their own hands as political agents in their daily lives, rather than pleading to an unresponsive politician or institution. The success of the campaign will depend on how well we as organizers can channel the energy of the current movement into this long-term, slow-build organizing once mobilizations start to dwindle. Most importantly, a BDS campaign with a mass approach can give socialists an opportunity to connect with a social base of Arab and Muslim communities that is currently deeply disenfranchised with the political establishment, more willing to mobilize around Palestine than virtually any other political issue, and hungry for ways to organize.