Socialists should build workers’ movements that model the society we aspire to win. As utopian as that might sound, these movements not only play a critical role in actual class struggle insofar as they maneuver and subvert control away from the owners of production, but also demonstrate in their design democratic worker-controlled socialism. This demonstration paves a significant path towards a communist horizon.

Emerge, a big tent communist caucus local to the NYC chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) of which I am a member, has a Point of Unity on labor (For Vibrant Labor Movements) that reads:

“We cannot build the future we want without a militant labor movement: a movement of workers as workers — waged and unwaged, professionalized and precarious — committed to class struggle both in the workplace and outside of it. Over the past half-century, American labor has been rendered largely toothless, thanks not only to the efforts of the reactionary right but also to anti-democratic “leaders” more interested in compromising with the ruling class than widening the field of struggle. Union bureaucrats who deflect the energy of the militant rank-and-file must be swept aside.

While established unions are key terrains for struggle, our fight should not be limited to them. If we are to rebuild a stronger, more vital labor movement in New York City, we must recognize the great swathes of our class who have no legal right to unionize at all. Farm and domestic workers are excluded from American labor law while undocumented and sex workers’ very existence are criminalized. Other low wage workers, like those in food service, are often ignored. Their organization is crucial to the revitalization of the labor movement as a whole — whether through traditional unions, workers’ centers, or other forms of self-organization not yet imagined.”

This point of unity clearly outlines many of the problems facing militant unionists, but what strategy does it commit us to? In my own opinion, I believe it’s a commitment to a strategy of Social Movement Unionism (SMU). SMU sees the encounter between unionism and social movements as a potentially powerful and pivotal moment that interrupts the traditional trajectory of bureaucratic labor politics. It engenders an opportunity for labor militants to engage in community and social justice-oriented politics that map onto workers’ struggles. It is a strategy that addresses the desperate need to build the bridge between the economic and the political if we are to begin constructing socialism in earnest. These are precisely the types of campaigns in which the NYC-DSA chapter has previously participated in coalition with community groups, political groups, labor unions, and workers centers (e.g. B&H Strike Support, The Tomcat Boycott, International Women’s Strike, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ Campaign for Fair Food).

SMU situates the weakness of both the American left and American labor movement in their seperation. As labor scholar Sam Gindin notes, workers involved in Communist “deep organizing” of the 1930s:

“…didn’t label their organizing strategy “social movement unionism.” They simply took it for granted that the workplace and the community overlapped and that employers’ ferocious resistance to the new unionism made worker-community alliances a necessity. Workers sat down in their workplaces, prevented banks from evicting people who were behind on their mortgages, and marched with the unemployed.”

By diagnosing the failures of both the American left and American labor movements in relation to each other, this strategy begins to advance a political answer to what the labor movement’s role in building socialism should be.

Embracing SMU doesn’t require us to reject other strategies and tactics. In fact, SMU is a versatile strategy that can incorporate a variety of subordinate tactics and strategies, including:

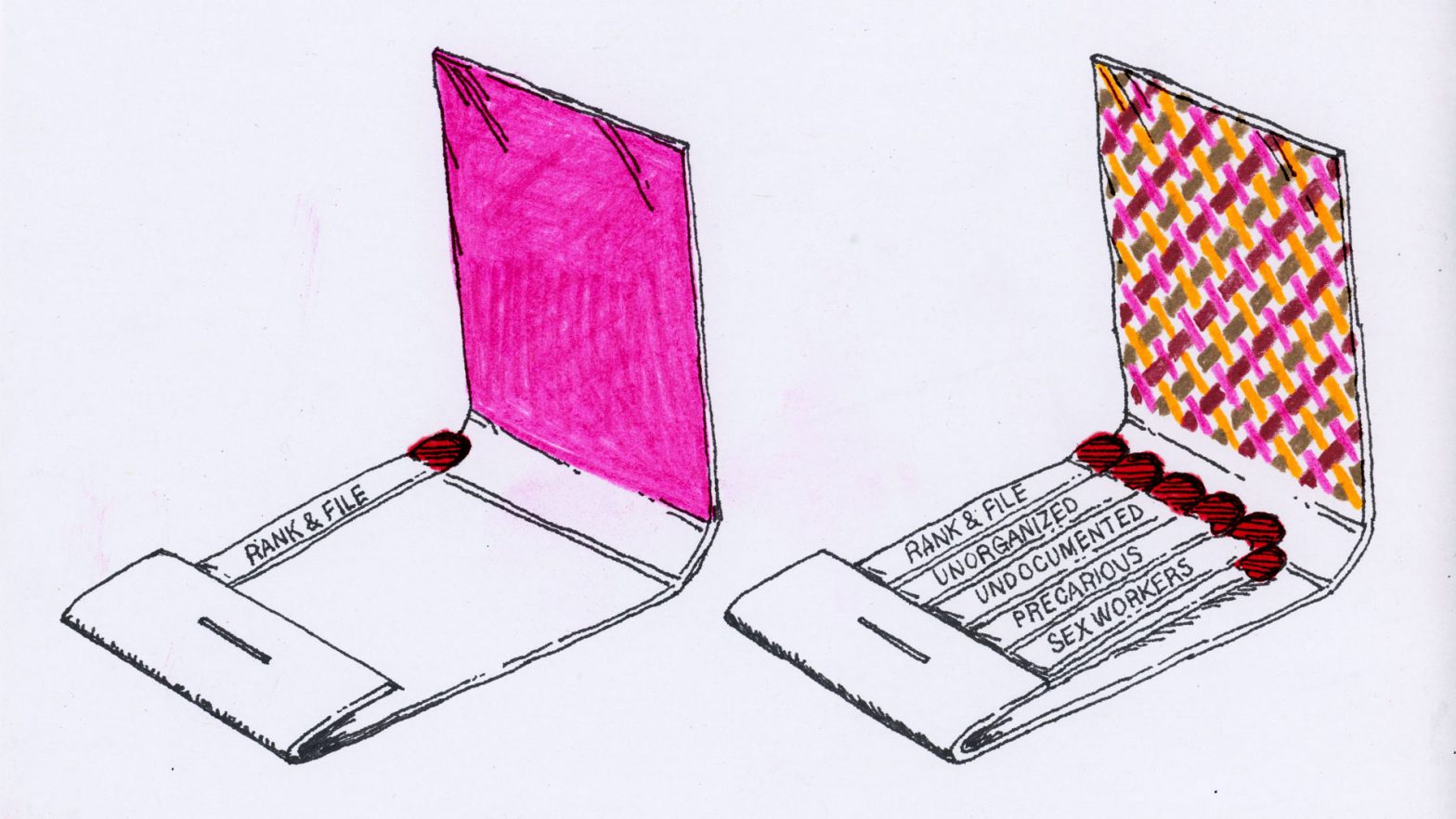

- A Rank-and-File Strategy

- Connecting workplaces struggle to social movements, building community unions that form alliances between unions and non-labor groups to affect change in the workplace and beyond.

- Building a workers’ movement across class fractures (waged, unwaged, professional, and precarious)

- Organizing the unorganized.

- Solidarity with workers whose self-organization must necessarily take different forms (farm, domestic, sex workers)

Perhaps the most prominent of these strategies is the Rank-and-File Strategy (R&FS) which the DSA adopted at its 2019 National Convention (though, significantly,a resolution to organize the unorganized was also adopted, among others). Kim Moody, a key architect of the R&FS, makes clear in his original pamphlet that contact with other organizational forms such as workers’ centers, community groups, and activist organizations are instrumental to the R&FS precisely because they further develop the militancy of rank-and-file leaders by exposing them to capitalist contradictions not often confronted by trade unions.

We would do well to remind ourselves exactly what the R&FS is for: the transformation of bureaucratic and undemocratic unions into class-conscious fighting unions. This effort is something we should of course be deeply committed to. However, as the socialist movement grows, it must confront what Moody names the ‘missing tasks’ of the R&FS. The original strategy was written at a low-tide of socialist activity, when the practical horizon of socialist activity was socialist regroupment, to transcend the micro-sect form. As DSA has largely accomplished this task, we need to move beyond this original horizon and ask: what is the specific intervention that a socialist organization like DSA, an embryonic mass organization, can contribute to labor militancy? And what does labor militancy contribute to socialist construction? These questions require a strategy built around labor’s role in the construction of socialism and not just a strategy to restore fighting unions.

Besides its silence on socialist construction there are certain structural problems that constrain the R&FS’s effectiveness in organizing, especially across disjointed working class elements. Where SMU emphasizes the mutually transformative nature of the encounter between unionism and social movements, the R&FS emphasizes a stageist vision of class and socialist construction (build the militant minority, then build the class, then build the party, then build socialism). However, the fact of imminent global environmental catastrophe makes a stageist approach less viable. According to Gindin, “To make social movement unionism a reality, we need an organization that can strengthen working-class capacities and propose long-term strategies for winning and exercising power.” He is here talking about a party, which I think skips over certain critical questions regarding organizational forms at the intersection of union-party-movement. However, I do want to highlight his rejection, which we should share, of stageism, as this is an implicit invitation to build such an organization concurrently with social and labor movements.

Additionally, we should consider the specific class composition of the reinvigorated socialist movement itself. It is largely concentrated in one class fracture, downwardly-mobile middle-class white millennials. A lot has been written about class fractures and their political effects, much of which I’d like to completely avoid. What I’d like to focus on instead is how this concentration affects the R&FS specifically: is any socialist organization situated in this milieu well-suited to launch a multi-faceted R&FS, or will their membership concentrate in one or two, highly credentialed, industries (as we are seeing with teaching and nursing in NYC-DSA)? If this is the case, then we need to ensure the simultaneous use of different strategies such as community unionism, direct recruitment of members from underrepresented unions, and, importantly, organizing the unorganized alongside the R&FS, to reach a large swath of working class fractures.

Historically only labor organizations have had resources to organize the unorganized, but as our movement grows this may no longer be the case. We are already starting to see glimpses of this in organizing drives in San Francisco (Anchor Steam unionization with ILWU). Rank-and-file organizing and organizing the unorganized can be mutually reinforcing tactics. Democratic rank-and-file control of labor organizations buoyed by shop-floor militancy and engaging in class struggle against capitalists better positions emerging organizing projects. New democratic organizing projects create a leftwing pole in the struggle against undemocratic unions and their labor bureaucracy.

That all being said, we must ardently defend the R&FS strategy as an important subordinate strategy to our larger vision of socialist construction from both its critics as well as reductive and opportunistic interpretations of it. The specifics of the R&FS are far from uncontested- even Moody has revised some of his initial arguments. The strategy of ‘bore-from-within’ to ‘vibrant rank-and-file democracy’ is not yet entirely formulated, nor could it be, as only the struggle itself can furnish it with concreteness. However, just because it’s a contested strategy doesn’t mean we should shy away from putting forward what we believe to be the correct vision for rank-and-file organizing:

- The working class can only become an agent of societal transformation through active struggle against the capitalist class and its state.

- Workplaces and specifically unions are the most immediately obvious sites of such confrontation because 1) the workplace often puts one in direct confrontation with members of the capitalist class and their functionaries and 2) the labor union organizational form allows workers to wage class struggle in a manner that can develop its future capacity. Importantly, however, they are not the only or even the most important of such sites of struggle.

- Socialists should enter industries to identify and develop a layer of the rank-and-file cadre that can serve as organic leaders. Whenever possible, Socialists should look into entering strategic capital choke-points (e.g. logistics, transportation, health, etc). However, coordinating socialists in such strategic sites is not the R&F strategy itself. The rank-and-file strategy can be carried out in any workplace or sector.

- It is this layer that is, in fact, the crux of the rank-and-file strategy and not necessarily the socialists who come into these industries or even the socialist demands they put forward.

- Because of low-levels of worker engagement in union activity (due to grappling with bare survival as well as depoliticization) collective action depends on the day-to-day organizing of this layer, or what is often called the ‘Militant Minority’: those who understand, are experienced in, and radicalized by class struggle (though who may not necessarily identify with an ideological project such as socialism or communism).

We must not confuse the struggle of a union caucus against an entrenched bureaucracy as the rank-and-file struggle itself. A caucus is only a vehicle for working class struggle, as is a labor union and as are political formations such as DSA. We must constantly prioritize the training, education, and empowerment of working and oppressed people. We must develop ways to incorporate the masses of workers into that struggle in ways that are not immediately self-evident or mapped.

SMU and the R&FS share a radical vision of deep and complex transformations of not only unions but unionism itself:

“The chief obstacle to real social movement unionism is resistance within unions to the all-encompassing changes it would require. Social movement unionism is not about labor supplementing what it is already doing (for example, with better policy proposals or new departments) or establishing “external” alliances with other movements. Rather, it’s about sparking a revolution inside unions — above all, by infusing them with class politics.” (Gindin)

Additionally, Moody has argued that worker struggles can be “rehearsals for revolution.” If that is the case, these rehearsals must take on the democratic, radical forms that we hope to see in our struggle against capital. Where labor bureaucrats have developed interests that run counter to class struggle, and often fight against it in favor of class collaboration, a communist workers’ movement should see formal organization — whether it’s a union, workers’ center, or some other formation — as nothing more than a vehicle for workers’ struggle, as instruments to help us occupy, and transform the terrain of struggle. Communists can and must once again resume organizing workers’ movements and orient such movements beyond mere short term economic interests by mobilizing past wage demands. They must now fight for militant, democratic, and revolutionary labor organizations.

The shared aim of the R&FS and SMU is to infuse class politics into trade-unionism as a means of developing the working class into a political force that can fight for direct workers’ democracy (“democratically administered social services” by public workers and democratic planning of our economy). However, this infusion of class politics and how this transmission is accomplished is itself problematic and requires strategic intervention. In other words, where these strategies largely differ is how they envision this transmission of class politics, the spark that transforms work-place demands into anti-capitalist politics.

*The author would like to acknowledge that this article was written in conversation with the work of sociologist Kate Doyle Griffiths and a draft of what would become “The Rank and File Strategy On New Terrain”, published by Spectre Journal.